Aarushi Lunia

The New York Times

Abstract: This paper examines the Supreme Court’s deployment of the True Indian rhetoric to critique judicial nationalism and its exclusionary impact on citizenship. By discussing the NRC, CAA, and electoral roll revisions, it argues that constitutional citizenship is increasingly conditioned on ideological conformity, undermining equality, dissent, and the civic foundations of Indian democracy.

Introduction

“You say I have got a homeland, but still I repeat that I am without it.”

– Dr. B.R. Ambedkar in his famous speech ‘Gandhiji, I Have no Homeland’

Citizenship has become a prominent issue of discourse. It is not just a theoretical debate anymore, but an alarming case at hand in present times with the enactment of new laws and policies by the present political dispensation. This concern is further exacerbated by the Supreme Court’s recent remarks in a case where they remarked “if you are a true Indian, you would not say all this” to Congress leader Rahul Gandhi when he made some statements with respect to the Chinese territorial excursions. The court went on further to suggest that such concerns should have been raised in the Parliament rather than through public platforms.

While technically this was the obiter dicta, it is particularly concerning because it is more than just a judicial commentary. It showcases an active effort by the highest judicial court and the protector of the fundamental rights of the citizens in creating an exclusionary criterion to determine the ‘Indianness’ of a person based on their ideological conformity. This danger of citizenship has resurfaced multiple times through the National Register of Citizens (‘NRC’), Citizenship Amendment Act (‘CAA’), and electoral roll revisions in Bihar, putting these people at the constitutional borderlines by making documentary proofs and ideological conformity the pillars of citizenship assessment.

This paper discusses this constitutional crisis through the Supreme Court’s recent use of a ‘true Indian’ rhetoric, relating it to broader exclusions by the NRC, the CAA, and the electoral changes in Bihar. It discusses the precariousness experienced by people who live on the borders of the constitutional order by arguing how the demands for documentation and compliance requirements produce instability for the marginalised. Further, the paper addresses the emergence of a normative idea of patriotism. And finally, it discusses the problematic judicial endorsements of citizenship on the notions of nationalism. Through this, the paper critiques judicial overstepping of boundaries and argues that Indian constitutional citizenship should not be made contingent on political loyalty, religion or ideological conformity.

Precarious Citizenship and the Constitutional Borderlines

The Constitution of India established citizenship on the basis of birth, descent, domicile, and residence. (See Article 5-11). The framers of the Constitution actively resisted categorising citizenship with a person’s ethnicity or religious beliefs. This founding principle reflected the constituent assembly’s commitment to creating what Jayal terms “a true republic of equals with a complex architecture of citizenship rights sensitive to the many hierarchies of Indian society.”

However, in spite of this constitutional mandate, citizenship in India keeps certain individuals on the margins. These people living at the constitutional borderlines refer to those whose on-paper legal status may be recognised, but their belonging is continuously challenged by the state practices and the political suspicions. This makes them constantly vulnerable to abandonment and extremities by the state, living in conditions of “suspended animation”.

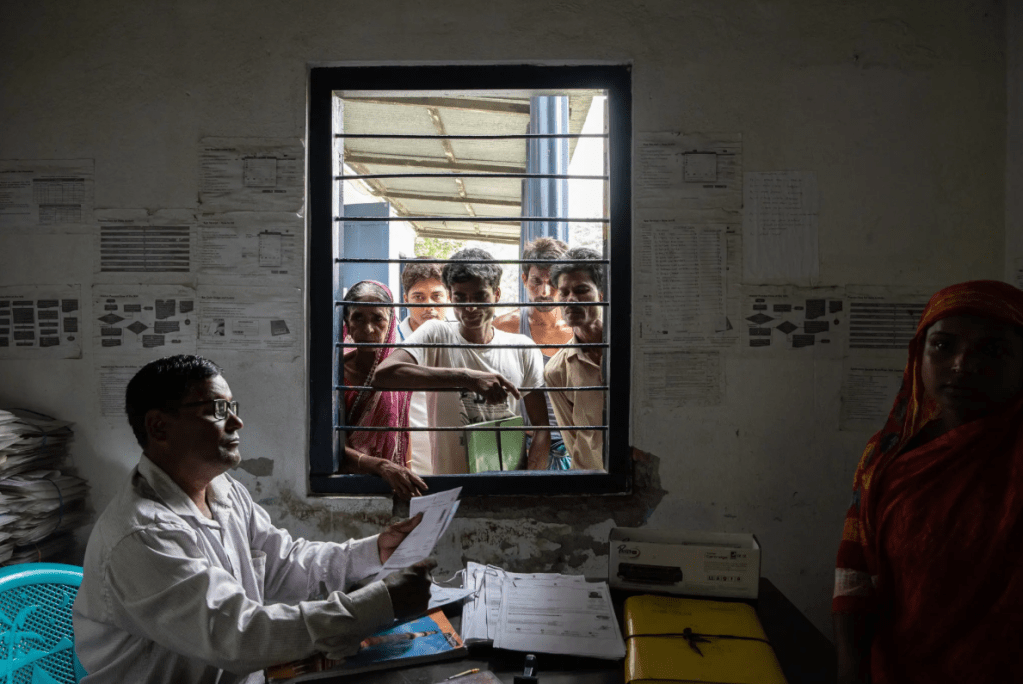

The Assam NRC gives the starkest example. In 2019, when the final register was published, 1.9 million people were excluded, many who had been living in India for generations. The NRC demanded proof by way of documents of residence prior to March 25, 1971 (See section 6A(3)(a)), a requirement that had a prejudicial impact on the poor, the illiterate, and women, who often did not own property or retain records involving schooling. Families that had worked the land for years were now suspected as foreigners. The UN Special Rapporteur on minority issues termed it potentially the largest exercise in statelessness since World War II.

NRC is not the only such event. In 2025, the Election Commission had proposed a Special Intensive Revision (SIR) of electoral rolls in Bihar on the grounds that duplicate or fake entries be eliminated. In effect, almost 4.7 million voters were struck off the final electoral rolls published on September 30, many from historically marginalized sections. This process was officially justified as removing deaths, migration and duplicates but in reality it disproportionately affected women, migrant, the rural poor and Muslim communities. Citizens were required to re-establish their citizenship, quite literally making the franchise a test of loyalty. This procedure marks a continuous precariousness as their belonging is constantly provisional whereas a Hindu male body is ipso facto a member of the Indian sovereignty. The fact that proof of citizenship is demanded itself turns a constitutionally guaranteed status into a privilege that must be verified over and over again.

As of December 2025, the Supreme Court has not given its final decision on this exercise in Bihar however has mandated certain requirements to ensure transparency in the process. While Phase II of SIR has begun in other states with relaxed documentation norms, the Bihar exercise continues to remain a contested precedent.

This precarity operates outside the above-discussed issues also. Citizens with disabilities represent yet another type of constitutional borderline. While legally citizens, their access to public life is mediated by regimes of exclusion as well as paternalism. Just as disabled individuals forever need to prove their capacity to access rights, other marginalised populations, such as migrants and minorities need to constantly prove their citizenship. The demand for documents turns into a demand for ‘ability’ which showcases the conditionality of constitutional belongingness.

Manto’s Toba Tek Singh offers a vivid allegory for this condition. The protagonist of the story, a patient in a mental asylum, finds himself suspended between two newly demarcated nations during Partition, unable to make up his mind if he belongs to India or Pakistan. Eventually, he falls down and dies on no man’s land. The story showcases the existential pain of being suspended between states because one refuses to belong to rigid nationalist boxes. Precarious citizens of this day such as the Assamese Muslims, disenfranchised people of Bihar, and stateless poor, echo Toba Tek Singh’s condition. They belong on paper but find themselves constantly suspended on the constitutional frontiers with no safety of equal belonging and never being able to achieve the security of citizenship that is mandated under the constitution itself.

Normative construction of Patriotism and Nationalism

- From Civic to Ethnic Nationalism

The Constitution of India envisages and provides for civic nationalism. It refers to the allegiance and belief in the Indian constitution, sovereignty, unity and integrity of the nation rather than one’s ethnic, religious or cultural identity. This reflects the vision of the constituent assembly for the creation of a democracy that accommodates the vast diversity of the country. However, recently a trend of ethnic nationalism has taken root. It refers to one’s citizenship being conditioned upon conformity to the beliefs of the majoritarian political and cultural norms. CAA represented this shift by offering expedited citizenship to Hindus, Sikhs, Christians, Buddhists, Parsis, and Jains from neighbouring countries while explicitly excluding Muslims. This Act marked the first time that a religion was made a determining factor in Indian citizenship law. It demonstrated that a Hindu refugee is presumptively Indian whereas a Muslim refugee remains a perpetual suspect. This reorientation is not just a legislative shift but a normative shift as well. It openly declares that certain religious identities align more naturally with the Indian nation than others.

While Indian citizenship always carried a tension between inclusion and exclusion, it has been weaponised in the present times by constructing dissent as disloyalty and conformity as true Indianness. Justice Dutta’s remark of a ‘true Indian’ has shown the contribution of the judiciary in this ongoing construction of normative standards of patriotism that go against the very principles of the constitution. The Supreme Court legitimatized the notion that citizenship requires uncritical support for the state narratives. It did so by suggesting that criticising the government policies on border security measures is not the trait of a ‘true Indian’. This shows a fundamental misunderstanding of the relationship between democratic citizenship and political dissent.

Thus, an evolution from civic to ethnic nationalism, takes place under the garb of the judicialization of patriotism, whereby the courts set about defining and providing for standards of national loyalty going beyond the compliance of law and extending the bounds of ideological acceptability. This judicialization generates new modalities of exclusion marked by non-alignment with the majoritarian understandings of proper patriotic expression. Through this, the courts are essentially establishing citizenship tests based on political acceptability as much as constitutional devotion.

b. Patriotism as Exclusionary Practice

Eric Hobsbawm, in Nations and Nationalism, describes how the European model of nationalism generated a normative concept of the ‘true patriot’ as one who subscribes to hegemonic cultural and political narratives while embodying loyalty to the nation as defined by those in power. This idea has been imported into postcolonial contexts like India, where nationalism has been mobilized as both emancipatory in the context of being anti-colonial but at the same time as exclusionary by requiring conformity with the majoritarian state political views. In the contemporary Indian context, patriotism is being recast as adherence to a Hindu majoritarian worldview.

Citizenship is not simply a legal status anymore rather it is being redefined as loyalty to the ideological project of the ruling political dispensation. The result is that a citizen who questions the CAA, NRC or some other state policy is termed as anti-national, and conforming with the state narrative is rewarded as ‘true patriotism.’ The danger of this normative framing is its elimination of citizenship as a civic-legal status, replacing it with an ideological-ethical identity. Citizenship shifts from being an Indian citizen in law, to someone who must be a true Indian in ideology. This puts both democratic opposition and critics in civil society at risk of having their citizenship questioned if they oppose government policy.

The concept of caste Hindu patriotism exemplifies how patriotism is racialized and encoded by caste. The national symbols, cultural practices, and political ideologies that are promoted as core to Indian nationalism will invariably reflect upper-caste Hindu norms. Muslims, Christians, Dalits, and dissenters are thus positioned outside this normative frame and their loyalty will be questioned despite their constitutional status. Patriotism thus shifts from a voluntary sentiment to an exclusionary practice which reproduces social hierarchies.

It is imperative that patriotism is distinguished from citizenship. Citizenship cannot and must not be dependent on the ideology of the government, it is a legal right that has its roots in equality. As has been argued by scholars like Harsh Mander and Mohsin Alam Bhat, a rights-based conception of citizenship ensures that dignity, equality and empathy are prioritised by the state. This right should be equally available to all the citizens irrespective of their caste, class, descent, race, gender, or ability. The biggest test of a constitutional democracy lies in its ability to include the weakest sections of the society and safeguard their rights.

Analysis of the Judicial Efforts to Define the Citizen

The Supreme Court’s characterization of the real Indian identity is not mere judicial comment, but real involvement in creating exclusionary definitions of patriotism to attack political adversaries and excluded communities. When the highest constitutional court suggests that some political criticisms are unpatriotic, it can encourage broader social and political exclusion, thereby pressuring people to conform to a single set of beliefs.

In the case of Abhiram Singh v. CD Commachen, the majority ruled that election appeals in religion, caste, or language were corrupt practices and that elections had to be ‘secular exercises’. It reinforced a normative, idealized vision of citizenship, one in which political identity must be stripped of caste or religious particularity. In doing so, the Court effectively silenced the political voices of marginalized groups, for whom caste and religion are not optional identities but lived realities tied to their experience of systemic exclusion. The dissent by Justice Chandrachud highlighted this risk by warning that this ruling would erase histories of oppression as it denies such oppressed groups the language through which they can articulate justice.

The Ayodhya judgmentalso mirrored judicial nationalism. While presenting itself as balancing Hindu and Muslim claims, its grant of the disputed site to Hindu parties sanctioned that the majority religion has a superior claim over a national space thereby further endorsing a hierarchy of belonging. This in fact sanctioned a form of judicial nationalism and reinforced the idea that the nation’s cultural and spatial identity aligns more closely with the religious majority. These cases illustrate how the judiciary itself institutionalizes majoritarianism through its normative understanding of who counts as truly “Indian”. This judicial construction of Indianness that is grounded in cultural homogenization transforms the secular constitutional project into a majoritarian constitutional morality. Thus creating a framework where neutrality is indistinguishable from dominance.

In the case of Md. Rahim Ali, although Ali was finally declared as a citizen by the court, it was pointed by the judge himself that the requirements of Section 9 of the Foreigners Act, places an unfair burden of proof on the individual. However, despite recognizing this arbitrary power under the statute, which provides the executive the authority to suspect a person of being a foreigner randomly. The judiciary still upholds the NRC process in the majority of its cases. By refusing to challenge the underlying presumption of guilt that the statute embeds, the judiciary transforms an executive instrument into a judicially sanctioned mechanism of citizenship regulation. In doing so, the Court’s reasoning goes beyond merely applying the law as it now participates in shaping the very logic of belonging thereby normalizing the idea that citizenship is contingent and must be constantly demonstrated by certain groups.

Similarly, in another case relating to citizenship, in Re: Section 6A of the Citizenship Act 1955, the supreme court upheld Section 6A of the citizenship act, 1955. In upholding this, the court acknowledged that the provision creates different classes of citizens and that too with differing degrees of rights. One such is denying the right to vote to certain categories of migrants for ten years. This creates a regime of differentiated citizenship, where migrants are classified into deserving and undeserving categories, each accorded varying degrees of rights. The court here did not introduce new distinctions but reaffirmed an existing political compromise that had long institutionalised the idea of unequal citizenship. However, by upholding this framework, the judiciary went beyond statutory interpretation and judicially entrenched a political arrangement, thereby transforming a temporary compromise into a constitutional principle. In doing so, the Court effectively participated in the construction of a hierarchical vision of citizenship, reinforcing selective belonging and legitimizing differentiated inclusion within the national community.

When read together, these cases reveal a growing judicial willingness to define Indianness in prescriptive terms. The language of being a true Indian, whether through standing for the anthem, refraining from political criticism, or displaying unwavering obedience to constitutional symbols, narrows the ambit of citizenship. When courts adopt exclusionary nationalist framings, it is likely that they would undermine the purely civic view of citizenship envisaged by the framers of the Constitution. Instead of defending the right to dissent and the different ways people can show patriotism in a democracy, such decisions represent a turn toward judicial nationalism. This leads to situations where the democratic institutions operate, although formally, they fail to check the powers of the majority as well as the rights of the minority. Such judicial nationalism restricts constitutional freedoms and undermines the basic fundamental idea of citizenship and its tenets.

Conclusion

The analysis presented demonstrates a troubling convergence of law and politics that creates a regime of precarious citizenship in India. This crisis is primarily driven by the emergence of judicial nationalism and the exclusionary effects of defining Indianness through ideological conformity, exemplified by the Supreme Court’s use of the ‘true Indian’ rhetoric.

The consequence of this shift is that people at the constitutional borderlines such as the Assamese Muslims, Bengali migrants, and disenfranchised voters in Bihar find their legal status being challenged perpetually. Mechanisms like the NRC and electoral revisions impose demands for documentation and compliance that disproportionately affect the poor, illiterate, and the marginalized, effectively turning a constitutionally guaranteed status into a privilege that requires verification constantly. This mirrors the existential pain of being constantly suspended on the constitutional frontiers.

Furthermore, the actions of the judiciary have contributed to the growing shift from civic nationalism to ethnic nationalism. This has been done by articulating prescriptive standards of patriotism, mandating outward displays of loyalty, and equating ideological non-alignment with a failure of ‘true Indianness’. This elevates non-justiciable fundamental duties into codified requirements of belonging and thus blurs the boundary between cultural conformity and legal obligations.

In conclusion, to fulfil and reinstate loyalty to the constitution, citizenship must be divorced from patriotism. Instead, it must be rooted in law, dignity, and equality. Belonging should not be a matter of subservience to political hegemony. The future of Indian democracy rests not on identifying who the true Indian is, but on whether the state remains true to its constitutional pledge of equality, ensuring that all citizens can claim their rights without fear of continuous suspicion and hierarchy.

Aarushi Lunia is a Third Year Law student at the National University of Juridical Sciences (NUJS), Kolkata. Her academic interests include constitutional law, legal theory, and alternative dispute resolution mechanisms, with a particular focus on their evolving relevance and contemporary necessity.

Categories: Legislation and Government Policy