Prabhu & Simone Avinash Vaidya*

Source: The Print

The judiciary has long stood as the beacon of justice and the guardian of core constitutional values. It is therefore imperative to uphold the integrity and calibre of its members, ensuring the highest standard. Over the decades, various statutory enactments and judicial pronouncements have attempted to maximise the efficiency of the judiciary by regulating the induction of judges at the lower and entry levels. In this blog, the authors highlight the critical importance of appointing highly qualified individuals, examining the ripple effect of such appointments on the judicial hierarchy from a bottom-up approach.

The spotlight is on the much-anticipated AIJA case, wherein the Apex Court has reserved its judgement. This piece analyses the rationale behind prior practice at the Bar being a mandatory prerequisite for writing the judicial services examination. The authors argue that the solution lies not in rigid practice mandates, but in incentivising judicial careers, by breaking the ‘glass ceiling’ for lower-court judges and mandating diversity quotas in High Court elevations.

I. Introduction

Should the mandate of three years of practice as an advocate, in addition to the existing requirement of a degree in law be reinstated to appear for the Judicial Civil Services Examination? (‘Exam’) A three-judge bench Supreme Court of India has examined this issue and reserved its judgements in this regard in the case of All India Judges Association v. Union of India.

This was first dealt with in 1991, in the case of All India Judges Association v. UoI (‘1991 Verdict’) wherein, to provide uniformity in the essential criterion for induction to the lowest rungs of the judiciary across different states, the Supreme Court mandated a minimum three years of practice at the Bar as an essential precondition to appear for the Exam. This directive was further justified on the basis that “unless the judicial officer is familiar with the working of the said components, his education and equipment as a judge is likely to remain incomplete.”

The 1991 Verdict was later undone in the Supreme Court’s 2002 decision in yet another All India Judges Association Case, (‘2002 Verdict’) wherein the three-year mandate was done away with based on the recommendation of the Justice KJ Shetty Commission Report of 1996. The observation made was that the quality of candidates appearing for the Exam was deteriorating steadily, thus compromising the quality of adjudication in the lower courts.

The removal of the mandate to practice thus rested on the anvil that after three years of practice, appointment as a judicial officer did not seem lucrative enough to young practitioners to attract them towards a career on the bench. The Shetty Commission Report noted that there was a deterioration in the quality of candidates appearing for the Exam. The State Governments were directed to do away with this prerequisite and amend the rules of the Exam, with the Supreme Court recommending that in place of three years of practice, one or two years of training be provided to the judicial officers.

This piece seeks to highlight how this case is an opportunity to appraise the incentives present for judges of lower courts. The authors first analyse the Supreme Court’s authority to decide on appointment matters which normally fall under legislative and executive domains. Addressing the High Court’s formulation of rules pertaining to eligibility, the subsequent section outlines variations in the criteria in states across the country, highlighting the need for standardisation. Next, prevailing trends of elevation to the High Courts are analysed from diversity and judicial reputation standpoints. The authors identify how the preference for practitioners over judges of the lower courts is reflective of the inclination towards experience in the Bar. The authors conclude by suggesting a reform in the elevation practice of the High Court that would generate an incentive trumping the apprehended effect of the three-year mandate.

II. Whether the Bench can set the bar?

Articles 233 and 234 of the Indian Constitution provide that the appointment to the posts of District Judges as well as to other posts under the Judicial Service of the State are made by the Governor of the State in consultation with the concerned High Court and that the power to regulate their conditions of service belongs to the executive and legislature. Therefore, if such a consideration falls under the purview of the respective State Governments, the question that emerges is whether the Supreme Court possesses the authority to dictate the conditions of such appointments.

This was addressed in a review petition filed by the Union against the 1991 Verdict, and the Supreme Court delineated the paramount consideration of the independence of the judiciary. It highlighted that denying the judiciary a role in matters pertaining to its service considerations would in fact be unconstitutional. The reasoning for this lies in the Supreme Court’s justification that the directions are essential to evolving an appropriate national policy, and the judiciary is thus nudging the other branches of government in this direction.

Similarly, vide the 2002 Verdict, the Supreme Court essentially gave effect to the recommendations of the Shetty Commission, presumably on the same justification of the judiciary maintaining its independence in this matter. Nevertheless, this has not precluded the High Courts from detracting from the 2002 judgement, as variations in eligibility criteria have been well-documented in each vacancy notification issued before conducting the examination. Such divergent practices are reflective of a broader issue, as there is a lack of uniformity in this approach across different jurisdictions.

III. Patchwork Practices Across High Courts

While hearing arguments in the instant case, it was observed that the criteria set by various High Courts across the country are wide-ranging, highlighting the need for uniformity. In the course of analysing the practice and rules across various states, it was noted that prior practice has been instituted as a mandatory prerequisite by multiple high courts to appear for the Exam, with the major bone of contention now being whether the duration of experience must be two or three years.

While Telangana has mandatorily provided for three years of prior practice in certain instances, states such as Sikkim, Haryana, and Chhattisgarh have not reinstated the 3-year practice rule. The recruitment process of judicial officers for the State of Gujarat was stayed by the Apex Court pending the decision in the present case as the Gujarat High Court did not lay down minimum years of practice as a condition of eligibility. The High Courts of Karnataka, as well as Andhra Pradesh, have put the selection process in abeyance awaiting the decision of the Supreme Court.

While dealing with challenge to the recent notifications regarding barring of law graduates not being enrolled with the Bar Council, the High Court of Chhattisgarhruled that enrolment must not be a criterion to appear for the Exam while noting that the enrolment of candidates as law graduates would not make a significant difference as they would ultimately be scrutinised in the same manner. However, the matter has been adjourned pending the disposal of the petition before the Supreme Court.

The state of Madhya Pradesh (‘M.P.’) has brought forth a rather unique eligibility criteria which states that the candidate should either be a practising advocate for 3 years or an outstanding Law Graduate with a brilliant academic career having passed all exams in the first attempt with a certain minimum score. The vires of the “Madhya Pradesh Judicial Service (Recruitment and Conditions of Service) Rules, 1994” (‘M.P. Rules’) were upheld by the M.P. High Court in the case of ‘Devansh Kaushik v. State of Madhya Pradesh’ (‘Kaushik’). The bench in Kaushik noted that the direction given in the 2002 Verdict was to amend the rules to enable a fresh law graduate, who may not have even put in three years of practice to be eligible to compete and enter the judicial service, if preferably two years of training has been provided to such recruits. The challenge to the MP Rules thus failed as they did not mandate for a candidate to have a three-year practice, while also not preventing an advocate with a three-year practice from competing, thereby balancing the dictate of the 2002 Verdict with the primacy of practical experience. The MP Rules have also been upheld by the Supreme Court in a challenge against them. In light of the same, the High Court of Kerala has also resolved to model its rules to provide for practice and a mandatory prerequisite to appear for the Exam.

It is thus evident that there exist differing practices across the nation, with some states such as Chhattisgarh, Sikkim, Haryana, etc. not mandating practice as a criterion, while certain states, like Telangana mandate it. Furthermore, while the Hon’ble Supreme Court has stayed the recruitment process for the State of Gujarat, states like Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh and Chhattisgarh have put the process in abeyance or have adjourned challenges to the process awaiting directions in the instant case, respectively. The sui-generis model provided for by the State of MP, after which the State of Kerala has resolved to fashion its rules seems like an interesting approach that may be undertaken by the States in the interim pending an authoritative judgement of the Apex Court.

This widespread variance and distinction in practice across the nation make it all the more important for the Apex Court to step in and lay down directions to clarify its stance and unify the criteria for the Exam throughout all the States. Keeping in mind this need of intervention by the Supreme Court, the authors have considered further relevant considerations regarding the induction of judges in the following part.

IV. Trends in Elevation

Judicial systems vary across jurisdictions and can be broadly divided into two distinct models of appointment. Career judiciaries prevail in civil law jurisdictions, where judges join the bench at lower levels and are promoted based on performance and experience. On the other hand, recognition judiciaries appoint their judges in recognition of their previous careers as practitioners or academics. Through this theoretical framework, it is observed that India follows a hybrid model which can be seen at the lower judiciary, as well as the higher judiciary levels.

For the lower judiciary or subordinate courts, judges are typically appointed through competitive examinations, and promotion is based on seniority and performance. However, this is variable, and district judges may be directly recruited from the Bar as well. For the higher judiciary, judges are either promoted from the lower judiciary or elevated from the Bar; in the case of the Supreme Court, a distinguished jurist may also be appointed as a judge. In practice, the lower judiciary is primarily career-oriented, whereas the higher judiciary is more recognition-based.

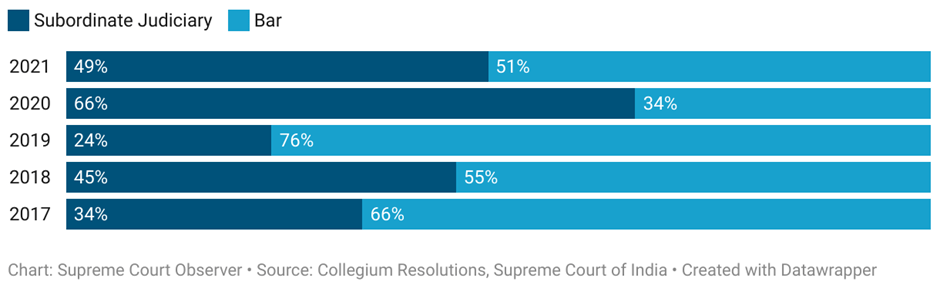

Recent research indicates that benches of the High Court are dominated by judges who have been directly elevated from the bar (‘Lawyer Judges’) while judges elevated from the lower judiciary (‘Elevated Judges’) constitute a smaller share. Furthermore, the bench of the Apex Court is adorned almost exclusively by judges from the High Court cadre, thus effectively carrying an even smaller share of Elevated Judges from the lower judiciary to the Supreme Court. Thus, if there is to be any reform in the system, it must be targeted at the High Court level. The graph below compares the number of Lawyers Judges and Elevated Judges as recommended by the Supreme Court Collegium for elevation to the High Courts.

The number of Elevated Judges over the years, though variable, has been relatively lower. Therefore, empirically as well as rationally, the stilted career growth and an effective glass ceiling that exists for judges of lower courts can discourage talent that was aspiring to write the exam. This contributes to the overall poor performance of the lowest rungs of dispensation of justice as is evidenced by a low disposal rate and soaring number of appeals resulting in extremely high backlog and pendency across all tiers of the judiciary. Therefore, the lower courts are trapped in a vicious cycle of underperformance and denial of promotions.

V. The Case for Diversity

Amid the plethora of criticisms and suggested reforms of the Indian Judiciary, one that has occupied the centre stage of discourse is regarding the lack of diversity in the higher echelons of the justice system. Diversity on the bench is multifarious including diversity on the basis of sex, caste, region, religion, etc. In a country strife with social inequality, it becomes all the more important for the judiciary to be inclusive and reflect the gender, religious, caste, and regional diversity and makeup of the country.

The long-standing tussle between the Indian Judiciary and Executive regarding appointments to the higher echelons of judicial offices is currently tilted in the favour of the bench with the Chief Justice of India having the final say in matters of judicial appointments. This therefore renders the judiciary answerable for the diversity or its lack thereof on the bench. So far, seniority has been considered the single most important and decisive factor in matters of judicial elevations and appointments with other factors like meritocracy, integrity, and most importantly diversity taking a backseat.

Diversity also becomes relevant from a judicial reputation standpoint, as this theory essentially posits that in recognition judiciaries, judges are hyperaware of their individual reputations and have an impact on the trust of the people on the judiciary as whole as well. On a more collective and institutional level, diversity is likely to enhance the reputation of the judiciary culminating in a stronger foundation of trust-building. Reservation in the higher levels of judiciary for the betterment of the downtrodden and unrepresented classes is a plea that has gone unanswered and despite various judicial pronouncements, criticisms, opinions, and legislative enactments, the issue of diversity seems to be one of the many places where the higher judiciary’s performance has been lacklustre.

VI. Conclusion: Elevating Judges as Incentivisation

The Chief Justice of India wields the power of the pen in deciding appointments, and the gavel now rests with the judiciary to settle this issue. The present case is a golden opportunity to address issues with diversity and incentivise the finest candidates to join the Bench.

The way forward is undoubtedly to ensure more diversity on the Bench, and an appropriate measure in this direction is to give higher weightage to a career judiciary form of appointment in the High Courts. One form of mechanisation could be to increase, possibly by means of carving out a quota, the appointment of judges from the subordinate courts to the High Courts.

Such quotas in recruitment are not alien to the Indian judiciary, as the 2002 Verdict has also issued directions on the share and manner of selection of the cadre of District Judges. Therefore, a parallel system for the higher judiciary would not be out of place, as it merely gives effect to the principle of elevation from the lower courts to the High Court, which has been enshrined in Article 217(2)(a) of the Constitution. Article 217 delineates the qualifications for appointment as a Judge of the High Court, providing that a person shall not be qualified unless they have either held a judicial office for a minimum of ten years or been an advocate of a High Court for the same period of time. This provision thus provides a Constitutional backing for the elevation of members of the subordinate judiciary to the High Courts, which has evidently been underutilised.

The higher scope for career growth would also offset the disincentive that the practice mandate is apprehended to cause. Diversity is also guaranteed in this regard, as the Exam provides for affirmative action in the form of reservations. Therefore, the proposed model would have the effect of ensuring greater diversity in the superior judiciary as well. As a matter of practice and convention, seniority is considered a key factor in elevation, and such a career judiciary-like promotion system fits this description perfectly.

Based on the high number of Lawyer Judges adorning the bench, supported by the opinions of academics and experts, Elevated Judges have not been the preferred choice of justices for the Higher Judiciary. Therefore, it follows to reason that a few years of practice at the bar is a preferred trait for judicial appointments. Furthermore, the Exam also provides for reservation and affirmative action for various communities and persons not aptly represented on the bench of the higher judiciary. If a higher number of Elevated Judges are preferred over Lawyer Judges (as has also been resolved to be attempted in the 2009 Chief Justices Conference but to no significant avail) then even despite mandating practice at the Bar as a prerequisite will attract high-performing candidates to the Exam and further ensure greater diversity on the bench provided that as a matter of practice and convention, seniority is considered as the primary factor for elevation, thus killing two birds with one stone. The proposed system would thus enhance the quality of candidates joining the judiciary at lower levels and resultantly alter the entire judicial system for the better.

Reforming the judicial appointment process is the need of the hour, as inefficiencies and delays pervade the system at all levels. Policy-makers must direct their focus towards incentivisation, as it can individually and institutionally promote efficiency with an increased awareness of their reputations. While this would fall within the domain of policy-makers, the present case places the Supreme Court in a pivotal position to give effect to a mandate that would undoubtedly enhance the quality of individuals joining the judiciary.

*Prabhu is an undergraduate law student at Hidayatullah National Law University, Raipur.

*Simone Avinash Vaidya is a second-year student at Maharashtra National Law University, Mumbai

Categories: Legislation and Government Policy