Matthew Waddington*

Legislative drafting in Commonwealth jurisdictions is undergoing significant changes with the advent of Rules as Code (RaC). A key debate centers on whether RaC initiatives can effectively handle discretionary provisions, particularly those using the word “may.” Drawing from work at Jersey’s Legislative Drafting Office, the article argues against the common assumption that RaC is only suitable for prescriptive legislation lacking human discretion. Through analysis of different types of “may” provisions—including permissive and potestative uses—it demonstrates how these can be effectively formalized and digitized using both deontic logic and if-then-else structures. The argument extends to suggest that legislative drafting offices should encode the logical structures of all legislation while being more precise in their use of “may,” following the modernization path that replaced “shall” with “must” in Commonwealth drafting. The research contributes to a broader understanding of how traditional legislative drafting practices can adapt to and benefit from computational approaches while maintaining necessary flexibility for human discretion.

A legislative drafting approach to Rules as Code

In the Computer-Readable Legislation Project at the Legislative Drafting Office in Jersey, we have been trying to incorporate the perspective of legislative drafters into Rules as Code (‘RaC’). As part of that, we have been working on non-technical guidance and training for legislative drafters in the Commonwealth to show them how the lessons of RaC and computational law can help to improve on the rigour and logical structure that they are already embodying in their drafting. We have also brought the perspective of legislative drafters to question the widespread assumption that RaC is only suitable for legislation that is purely “prescriptive” in that it does not require any human discretion, which legislative drafters commonly flag with the word “may” (or “reasonable” – see below on vagueness). One of the points where these issues come together is in the way legislative drafters use “may”, and how that can be formalised and digitised, and then improved.

This piece looks at some issues with how “may” is used by drafters, and encoded in RaC, in legislation drafted in the Commonwealth tradition. It explains why we see provisions with “may” as suitable for RaC, and why we do not see RaC as limited to “prescriptive” provisions. It then looks at some lessons that can be learned from “deontic logic” (as used in many RaC approaches) for how legislative drafters use “may” for giving permission (and how a computer can understand that), and at whether a simpler “if-then-else” logic is more appropriate for capturing the logical structures of “may” provisions. It then looks beyond the permission cases to see what has been learned from computational law about other uses of “may”, including those that grant powers but also those that are purely about factual possibilities, to recommend more rigorous use of “may” (in a way that reflects the use of the more rigorous “must” instead of “shall”).

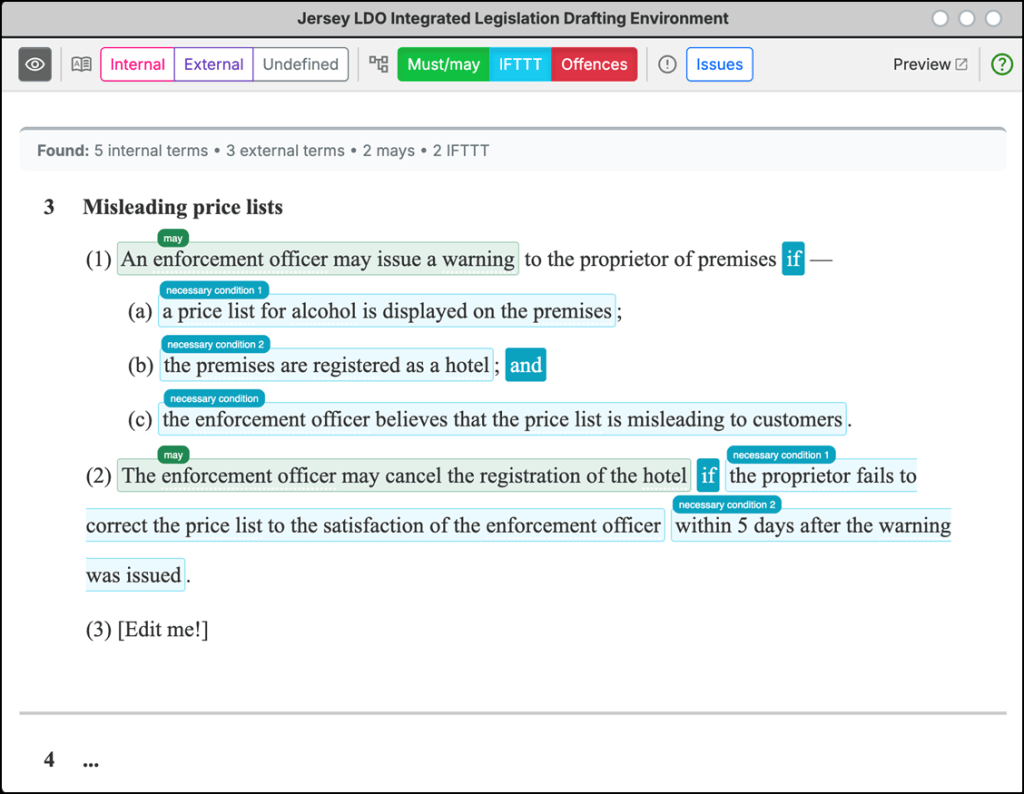

As one practical aspect of incorporating the perspective of legislative drafters, we have been looking into the possibility of an Integrated Development Environment-like tool for legislative drafters,[1] on which we will now be working with the Centre for Digital Law, at Singapore Management University, till June 2025. We have an interactive mock-up of some of the functions of such a tool for legislative drafters, which includes two examples of “may” powers. The idea is that legislative drafters should find it easy to mark up types of provision, including “may” provisions, while they are drafting in such a way that a computer can then follow the logical structure that has been created.

Figure 1: Interactive Mock-Up

In the Commonwealth, legislative drafters have to build new legislation piecemeal into the existing legislative structures but also into common law structures, which gives us a distinctive approach (as, for instance, where a draft says that a Minister “must” do something, but is silent about the consequences of any breach, because it leaves it to the common law to apply the principles of judicial review and administrative law). In modern Commonwealth drafting, the trend has been towards standardisation, simplification and increasing rigour, in a way that makes it easier to identify logical structures and flag them with mark-up in the text. So what are the structures that involve “may” and what have we learnt about them that is useful to legislative drafters and other lawyers, as well as to developers?

Is RaC only suitable for “prescriptive” legislation, and does that rule out encoding “may”?

There is a widespread assumption amongst those looking at RaC that RaC is only suitable for what they call “prescriptive” legislation, which might mean that “may” provisions would be inappropriate for RaC. For instance PWC recently claimed that “Translating legislation into machine-readable code for RaC is more effective with specific and clear rules. … rules open to interpretation or discretion pose challenges due to their subjective nature”. The underlying assumption seems to be that RaC is purely about being able to automate processes without any human input, and that this only works where the legislation is “prescriptive” in avoiding any discretion (including the discretion to interpret).

Our project takes a different tack, in that we believe RaC is suitable for all kinds of legislation, including legislation that other people would not call “prescriptive”, but also in that we question whether those people are clear about what they mean by “prescriptive” anyway. In fact, PWC’s claim included a reference to a piece by Salsa Digital, which in turn references one of the earliest RaC initiatives in New Zealand, which specifically said it “explored developing code for an area of legislation requiring significant human judgement to test whether it is difficult to code, and found it was no different or more complex than other rules”. We are concerned that those working on RaC today should not lose sight of this early recognition that RaC is useful even for legislation that requires “human judgement”, which people might see as not being “prescriptive”. Our different perspective comes partly from our approach to the questions of which aspects of the legislation are going to be coded and what use the coding will be put to.

- Aspects – We want to see legislative drafting offices publishing encoded versions of all legislation, but only of its logical structure (not for instance encoding a subject matter expert’s explanations of the effects of the legislative provision). In this, we see legislation as declarative of legal effects, rather than as prescribing a set of processes (that a developer can then encode and automate) or even primarily setting out normative orders (which a deontic logician would recognise – see below).

- Use – Our main interest is not in automation of some process that complies with legislation (executing the legislative code, as developers might see it). Instead, it is in just automating a system to give help to people to understand the legislation and its application to their scenarios (though of course that might in turn help someone else who wants to automate an aspect of the legislation).

To understand this idea of automation at different levels, it is worth expanding on Genesereth’s 2015 analogy of “the cop in the backseat”. He imagined car software that would tell the driver the speed limit for the road the car was on, which he compared to having a police officer on board. But that is now a common feature of the software for ordinary cars, and it is more like having a driving teacher on board rather than a police officer. It is also like the explanatory software that our project is interested in. Taking the analogy further, even without thinking about self-driving cars, it is now very easy to imagine software that would trigger a speed limiter if you tried to accelerate to a speed above the road’s speed limit, physically preventing you from committing a speeding offence. The analogy of a police officer would perhaps be more appropriate for software that did not prevent you exceeding the limit, but instead sent a report of your speed and location to the nearest police patrol (so they could decide whether to intervene, and you could explain the emergency or other reason that you believe means your speed ought to be overlooked). If we imagine police without discretion (an unrealistic aim of course), then the analogy would instead be software that automatically triggered sending you a penalty notice, like an onboard equivalent of a modern speed camera (perhaps with some human review first, and in a legal system where you can challenge the notice).

It is true that if you wish to automate to the deepest level possible then you will find that that works best with “prescriptive” legislation, where there is no need for human input. But it is worth unpacking the different strands that people are lumping together with that word “prescriptive” in relation to the legislation.

- One strand of what people mean by “prescriptive” is about the input, in the sense that the legislation is not vague or discretionary in anything that determines whether or not a “must” or “must not” applies. There is often confusion between ambiguity and vagueness, and about the prevalence and use of vagueness. The classic human input element is where the legislation expressly calls for something to be decided by an official (not just checking and acknowledging objective facts). But there is also an implied element of human input, of which the classic case is “reasonable” – where it would be for a (human) court to decide what is reasonable in a disputed case. Vagueness is best seen as a spectrum though, with “reasonable” at one end and mathematical expressions at the other, but in between are most of the words that we use to describe the rest of the world. That there is inevitably some degree of vagueness even in a word like “vehicle”, and there is always a need to have human native speakers of the language to give undefined words their ordinary meaning in the context. This is not about the use of “may” as such, when that is the effect that is the result of more or less vague conditions.

But another strand is about the legislation being focused on an output that is an effect about what “must”, or “must not”, be done, and limiting effects that are about what “may” be done. Then perhaps the software itself can automatically do what “must” be done (or prevent what “must not”), as in the idea of the car that has an automatic speed-limiter linked to the system that recognises each road’s speed limit..By contrast, only strong automation enthusiasts are going to think that AI or other software should be choosing whether to do or not do something that “may” be done. In the car analogy, on a 60mph road the driver “may” drive at 40mph or 50mph or any other speed under the limit. It would be odd to think that the car software would automate the choice of speed for a human driver, but of course in a self-driving car the software is making exactly that choice and there is no human driver who is subject to the legal obligation not to speed. But the attraction of automation is why (apart from the opportunity to show off computers’ ability to calculate amounts of money) much of RaC has focused on social security benefits legislation, which obliges governments to pay money to eligible citizens who apply for it. In that case the government is the person who “must” (and they can be assumed to want to comply), and what they “must” do is pay money (which can be done digitally), so compliance can be automated in that the required payments will be made without further human intervention or enforcement of the duty to pay.

An additional perspective, relevant to legislative drafters, is in how we should draft new legislation. In Denmark and the EU there is a movement to produce “digital-ready legislation”, by keeping both vagueness and discretion to a minimum in favour of clean prescription. But this is really no more than the tension that has always existed in legislative drafting and policy-making for legislation. Policy officials always want to be sure their policy will be carried out, but they have to balance over-specifying, which risks unintended consequences, against giving themselves broad discretion, which means (under administrative law principles in Commonwealth countries) that they will need to take individual circumstances into account instead of being able to claim legal backing to apply the blanket policy they want. That seems to mean there will be a limit to how far this approach can be taken, so there will always be the question of legislation that includes both vague terms and other forms of human input, and that leads to provisions that someone “may” do something.

Where this leaves us is that there is plenty of scope for encoding in all legislation, if we are not chasing the dream (or nightmare) of full automation of all processes set by legislation. Our project believes that legislative drafting offices should be aiming to encode the if-then structures in all legislation, with the automation limited to safely taking human users from one human input point to the correct next one (depending on the last human input), navigating the often complex logical structures that are needed to cope with the complexity of human life.

What this approach results in is a reasoned statement about how the legislation applies to a given scenario, rather than an attempt to bring about the effect required by the legislation. The best current example of this is DataLex, where you can try an automated questioning system that reaches a conclusion about how the legislation applies to your scenario, which it can then explain in terms of the logical steps it took to reach each set of conclusions to be drawn from your human input in your answers. The legislative drafting office would then publish this slim version of the coding as a shared resource both for those who want to work out how the legislation applies to them and as a common starting point for those who want to develop more sophisticated software to automate execution of some tasks in compliance with the legislation. The version would not have the status of enacted law, but would have a similar status to official “explanatory notes”, and would not be adding a layer of interpretation any deeper than what the drafter was relying on to create the draft (such as the principle that the same word has the same meaning).

Deontic logic or if-then-else – the logic of “may” (and “must” and “must not”)

So, if “may” provisions are appropriate for RaC after all, what can we do with them in RaC, and can “deontic logic” help with that? Symbolic formal logic is a useful tool for legislative drafters to analyse the logical structure of their drafts. Deontic logic is a type of logic that deals with obligations, prohibitions and permissions. In our project we find it useful as one tool for clarifying what “must”, “must not” and “may” are doing in a draft, but not necessarily as the main tool (we tend to go with Robert Kowalski, who sticks to if-then in his Logical English). The drafter’s “must” and “must not” are relatively clear concepts, with reasonably easy mapping to deontic logic’s obligation and prohibition. Their negations are similarly clear, although we do not have standardised ways of expressing them in our drafts. When we want to say it is not the case that a person must do an act, we cannot say “not must” so we say something like “need not” or “is not obliged to” (or other expressions that lose the link to “must”, against our normal practice of using the same word for the same thing). Expressing the negation of a prohibition is even more awkward – we cannot say “not must not”, so we can say something like “is not obliged to refrain from” doing the act.

In deontic logic, “may” can be compatible with “must” (if we oblige you to do something, we also need to permit you to do it). But in a legislative draft if we mean you must do something we will say so, and we will save “may” for when you are free to choose whether to do or not do it. So that is the combination of the two awkward expressions – “the person is not obliged to do X, and the person is not obliged not to do X”. When drafting, we need to remember that “the person may appeal” implies also “the person may not-appeal”, as in “may refrain from appealing” (rather than “may not appeal”, which unfortunately can be read as meaning “must not appeal”).

What can be gained by looking at how “if-then” structures relate to deontic logic, and adding in the computing idea of “if-then-else” (“else” marking the effect if the conditions are not met)? In the Commonwealth tradition a legislative provision should create a legal effect. Most also set out conditions that have to be met for the effect to apply (and our project’s main interest is in analysing them as inter-related if-then propositions). That means they have an if-then structure, translatable to formal propositional logic. But the Commonwealth legislative tradition also avoids free-standing “must” and “must not” – the drafter should provide a consequence for breach of the “must” or “must not”. The consequence need not be expressly stated, as long as the drafter is satisfied –

- that the common law implies a clear enough consequence – as with obligations imposed on public bodies, where the legislation often leaves it to administrative law to decide the consequences of non-compliance;

- or that the context does so – as when requirements are imposed on how an application is made, with the implication that otherwise it does not amount to a valid application and does not have the consequences that flow from a valid application – but drafters have long been warned about over-reliance on this, see Duncan Berry’s article in April 2012’s Loophole.

Our project is advising legislative drafters to tighten up on their “else” – ensuring it is clear what the alternative effect is when the conditions are not met for the effect that is stated. Also, if the stated effect is that a person “must”, “must not” or “may” do an act, then we need to tighten up on ensuring it is clear what the effect is when the person does, or does not, do that act.

That covers how we deal with “may do” when it is used just to mean “is neither obliged nor prohibited to do”, but is that the only way in which we actually use “may” and is it the only way in which we should use “may” if we want to take advantage of the benefits of RaC?

Legal formalisation – clarifying whether the drafter is using “may” for a permission, power or possibility

In fact, of course, deontic logic’s permissive “may” (neither obligatory nor prohibited) does not tell the full story for us, as there are other sorts of “may” in law. We turn now to look at other ways in which may is used, and how it can be formalised, to deal with “may” as granting a power, and to suggest that we should avoid using “may” to refer to mere practical possibilities.

Our approach to increasing rigour in the use of “may” has its roots in the already increased rigour in the use of “must”. In modern Commonwealth legislative drafting we have moved away from “shall” to “must” (see sections 5.3 and 5.3.1 of the Commonwealth Legislative Drafting Manual). That has helped us see more clearly what “must” provisions are doing and how they differ from “is” provisions (we used to say “shall mean”, “shall come into force”, “shall not be valid”, none of which can be replaced with “must” because they are doing a different job – see sections 3 and 4 of my 2022 preprint). Legislative drafters next need to do a similar job in tightening up and clarifying the different things they mean when they say “may”. For more on this see section 4 of my 2024 preprint and our project’s example of problems with “may” in a review provision.

As long ago as 1913, Hohfeld produced a logical scheme in which he distinguished rights, privileges, powers and immunities, all of which could be rendered in legislation with a “may” construction (or with a “must” provision in many cases, where one person’s “may” is another’s “must”). More recently Sartor, Governatori and others have analysed different types of legal provisions, and particularly different types of “may” provisions, but covering a much wider range than is used in modern Commonwealth legislative drafting.

For an example, here is an imaginary pair of provisions containing three instances of “may” –

“The inspector may grant an exemption to a farmer. If a farmer holds an exemption, the farmer may import any animal, despite section 5 (prohibition of import of unhealthy animals) and regardless of whatever may be the health status of the animal.”

The first distinction (the ancestor of which is present at the start of official legislative drafting in Coode in 1852) that we take from Sartor is between “constitutive” and “normative” provisions. This reflects the point mentioned above about the way that dropping “shall” led to seeing a difference between “shall mean” (now rendered as “means”, not “must mean”) and “shall grant” (now rendered as “must grant”). The former is constitutive, and takes effect by operation of law, whereas the latter is normative and can be breached. The border between the two is not a bright line, in that “An enforcement notice must contain information about the right to appeal” seems to be in the normative camp (it can be breached), but is probably really constitutive if what it effectively means is that a defective notice will not count as a notice at all (or at least will not have the effects that an enforcement notice is otherwise given). This works similarly for “may”, for example in “An enforcement notice may state a time limit within which steps are to be taken”, the “may” is about what does and does not count as a valid provision in a notice, and it will be linked to some later provision about an obligation to take the steps.

Then Sartor and the other modern theorists distinguish between different types of normative “may” – particularly “permissive” and “potestative” uses.

- In the Commonwealth context the effect of the common law background is that permissive “may” provisions are secondary to “must” and “must not” in legislation. That is because legislation should normally be changing the law rather than re-stating it, and the common law position is that natural persons are already free to do, or not do, whatever they like unless prevented by a legal prohibition or obligation. So the permissive use is as an exception to an obligation or prohibition imposed elsewhere in the legislation or in the common law (the exception to a “must” or “must not” can bring you back to “may”). In our example this is the second “may” – the farmer “may” import an animal as an exception to a prohibition in s5. The drafter should be satisfied that the link to the obligation or prohibition is clear enough, and the coder should look for ways to mark up that link.

- The potestative use is where the effect of someone doing what they “may” is that someone else (or sometimes the same person) has their status changed in relation to what they must, must not or may do. In our example this is the first “may” – the inspector may grant the exemption. That is not really making an exception to some prohibition on granting exemptions. Instead it is giving the inspector the ability to change the farmer’s status – if the inspector does not grant the exemption, the farmer remains prohibited by s5, but if the inspector does grant the exemption, the farmer ceases to be prohibited by s5. Again the drafter needs to be satisfied that the link is clear enough. It is also worth noting that the provision could instead have said that, if certain conditions are met, the inspector must grant the exemption – we would not normally call that a power, because it is an obligation, but it too has the same effect of changing the farmer’s status (but in many cases we might instead provide that the farmer is automatically exempted from the prohibition, instead of requiring the inspector to grant the exemption – as it is not necessarily clear what the intended effect is if the inspector fails to grant the exemption).

Neither the permissive nor the potestative cases require the use of “may”, as each could instead have been rewritten without it – our example could have said “Section 5 (prohibition of import of unhealthy animals) does not apply to a farmer in relation to the import of an animal, if the inspector notifies the farmer that the import is exempt, regardless …”. This makes it much more convenient to analyse these sorts of provisions in if-then terms (while retaining the word “may” if it is present), rather than worrying about whether they are true instances of some ideal form.

Unfortunately, it is still common for legislative drafters to use “may” in a sense that is neither normative nor constitutive, but is just about factual possibility. This is the third “may” in our example – “regardless of whatever may be the health status of the animal”. The other classic use, now frowned on as redundant by many legislative drafters, is “as the case may be”. Our project recommends more rigorous use of “may” for where it does carry more significance. It is almost always possible to redraft to remove “may” from this sort of provision – in our example it could be “regardless of the health status of the animal”, or at least “regardless of whatever is the health status of the animal” (thinking back to “shall” being replaced by “must” or “is” depending on its meaning).

We could go on to look at “may not”, and whether its legitimate use might be a flag for a need for another categorisation of “may”, but this is all there is space for, for now. To recap, then, there is much that legislative drafters can learn from logicians and computer scientists, but also much that the technical people (and many of the lawyers) working on RaC need to learn from legislative drafters, at least for legislation in Commonwealth countries. There is no need for RaC initiatives to shy away from anything that is not “prescriptive”, as long as everyone is clear that it is worthwhile to enable computers to follow the logical structure of legislation. That has a value that is different from automating compliance with the legislation, which is a step that should only be taken with great care in those cases where it is appropriate. If we take the approach of capturing just the logical structure of all the new legislation that we draft, that will enable a computer to explain the logical structure of legislation and guide a human user through questions, as well as helping legislative drafters to avoid mistakes. That approach can capture the logical structures that we represent in drafts with “may” just as it can for those with “must”, but it also calls for legislative drafters to take further steps in their ongoing history of increasing the rigour of their drafting.

[1] Integrated Development Environment is a form of software application that provides comprehensive facilities to computer programmers for software development. This includes a source code editor, build automation tools, and a debugger, helping the developer to write code that is workable. Legislative drafters currently use software that helps them to format and number their drafts correctly, but an equivalent of an Integrated Development could take that further to help the drafter to write legislation that is workable (in avoiding logical contradictions, ensuring defined terms are used correctly, and enabling the drafter and policy officer to check how the draft applies to given scenarios, and so on).

* Matthew Waddington is a legislative drafter (since 2004) and English solicitor (since 1990, now non-practising). He leads the Computer-Readable Legislation Project at the Legislative Drafting Office in Jersey, which is currently working with a team at the Centre for Digital Law at Singapore Management University.

Categories: LSPR's Blog Symposium on “Rules as Code”